What is ‘Cap Sur’?

These are articles written by the naval architects, designers and engineers at Vincent Lebailly Yacht Design. These articles deal with various conceptual subjects (nautical, of course) and take a critical look at the technical, ergonomic and stylistic solutions offered by today’s designers and builders.

In this article, we take a look at the motorisation of catamaran sailing yachts.

Using theory, tests and photos, we will review the existing solutions for powering a blue-water sailing catamaran and put forward our vision of a preferred solution. We will then argue for its presentation, taking into account essential concepts such as cost, efficiency, weight and maintenance.

Introduction:

Most manufacturers of catamarans for pleasure craft equip their boats with two identical propulsion engines.

There are a number of reasons for this symmetrical design:

firstly, for the user:

ease of use is a key factor in the choice of this technical solution. The two engines are positioned in the same place on each hull and have the same power. As a result, the boat behaves in virtually the same way whether it’s pivoting to starboard or port. This is all the more appreciable in the charter world, for which the majority of these catamarans are built. Identical twin engines mean that manoeuvres are “symmetrical” and the boat’s engine performance is optimally balanced, especially when manoeuvring in port with skippers and crews who have to take control of the boat from the very first manoeuvre.

Having both engines on board is also, and above all, a safety feature. The boat’s autonomy is preserved in the event of the failure of one of the two engines, thanks to the propulsion of the second engine, which is identical. A catamaran with two engines also means less propulsion, working on two engines rather than just one.

From the builder’s point of view, this twin-engine design also offers a number of advantages:

Optimised, calibrated construction with identical mounting in the port and starboard floats.

Identical maintenance by the technicians, with standardised spare parts common to both engines.

However, before any mechanical considerations, a sailing catamaran remains a sailing boat in its own right. Like its monohull counterparts, which are almost 100% powered by a single propulsion engine, a sailing catamaran moves (or should move) mainly by means of wind thrust. Just like a monohull, it would therefore be entirely conceivable to turn a catamaran into a sailing unit equipped with a single propulsion engine, with all the advantages that this configuration provides.

This is the thesis we will defend here:

1. The harmful effects of ‘identical twin engines’?

Because having two identical engines also means higher costs for the future owner. Two 20hp tehrmic engines will always cost considerably more than a single 40hp engine.

Then there are the purchase prices for peripheral equipment that add to the bill (propeller, shaft, various supports, exhausts, etc.). You also need to add installation times, which are roughly the same for a 20hp engine as for a 40hp engine. So if you multiply the number of engines by two, you have to add up the time needed to align and install the water intakes (for a shaft line engine), fit the exhausts, connect the diesel circuits and then the various wiring (electricity and engine controls etc.)… all hours that are expensive for the manufacturer and which are ultimately billed to the shipowner.

Having two propulsion engines also means a significant increase in the boat’s weight. By way of comparison, taking our example above: a 20hp Yanmar engine in sail drive represents a weight of 140kg (equipped with its sail drive). To this must be added accessories such as the propeller, exhaust, wiring, etc. Two 20hp Yanmar engines will therefore represent a total approximate weight of 300kg dedicated to propulsion. A 40hp sail drive engine from the same brand has a net weight with sail drive of 236kg, giving a total weight of 250kg once equipped. This represents a significant saving of 50kg for the boat, or 20% of the total weight of the propulsion system.

As explained above, maintenance is certainly standardised and simplified for technicians when two identical engines are installed, but it is also more costly, with twice as many filters to maintain or even change if necessary, two stuffing boxes (in the case of shaft lines), twice as many nipples, exhausts, valves etc… so there are twice as many risks of water ingress that need to be checked regularly.

This ‘identical twin engine’ also leads to greater vibrations in the boat’s structure, with noise pollution coming from both floats, affecting all of the yacht’s cabins.

So it’s easy to see that in terms of weight, cost, risk of nuisance and maintenance costs, ‘identical twin-engine’ is potentially a penalising solution for the shipowner.

2. What alternative solution?

Like a monohull sailing boat, a catamaran can perfectly legitimately be fitted with a single inboard propulsion engine, positioned in one of the two hulls only. If a sailing monohull can move with a single propulsion engine, why shouldn’t a catamaran?

Nowadays, the reliability of properly maintained inboard engines satisfies 99% of sailboat monohull builders who have made this choice (there are still a few mostly custom-built units (like our ISMERIA59′) that opt for twin engines, but this remains marginal).

Why shouldn’t a catamaran benefit from the same safety guarantees with a single propulsion engine?

The concept is to fit a single propulsion engine to a single float. The engine is therefore offset from the ship’s axis and we will analyse the impact of this on the behaviour of the yacht.

First of all, the advantages of such a configuration:

In terms of noise comfort, vibrations and noise are localised in a single float of the boat’s structure. If the engine is located in the starboard float, then the port side fittings will be affected very little by the noise.

Furthermore, the geometric layout of the engine in the float will only have an impact on one float. We’ll therefore be giving the engine and its peripherals a ‘real place’, with provisions (doors, front and rear access, ventilation) to enable proper maintenance. The engine is also potentially better placed, ideally more in the centre of the length of the float to limit the effects of inertia of distant masses.

Having a single propulsion engine also simplifies onboard maintenance, as there is only one inboard engine to drain, maintain and check. The number of through-hull fittings and other pumps is halved, which reduces the risks and makes them easier to control.

As explained in the previous chapter, the purchase of a single engine not only saves money, but above all reduces the overall weight of the boat.

It is now perfectly legitimate to wonder about the behaviour of the boat affected by :

– The imbalance in the transverse trim of the boat with a single mass so eccentric transversely

– A single propulsion thrust that is eccentric in relation to the axis of the boat itself.

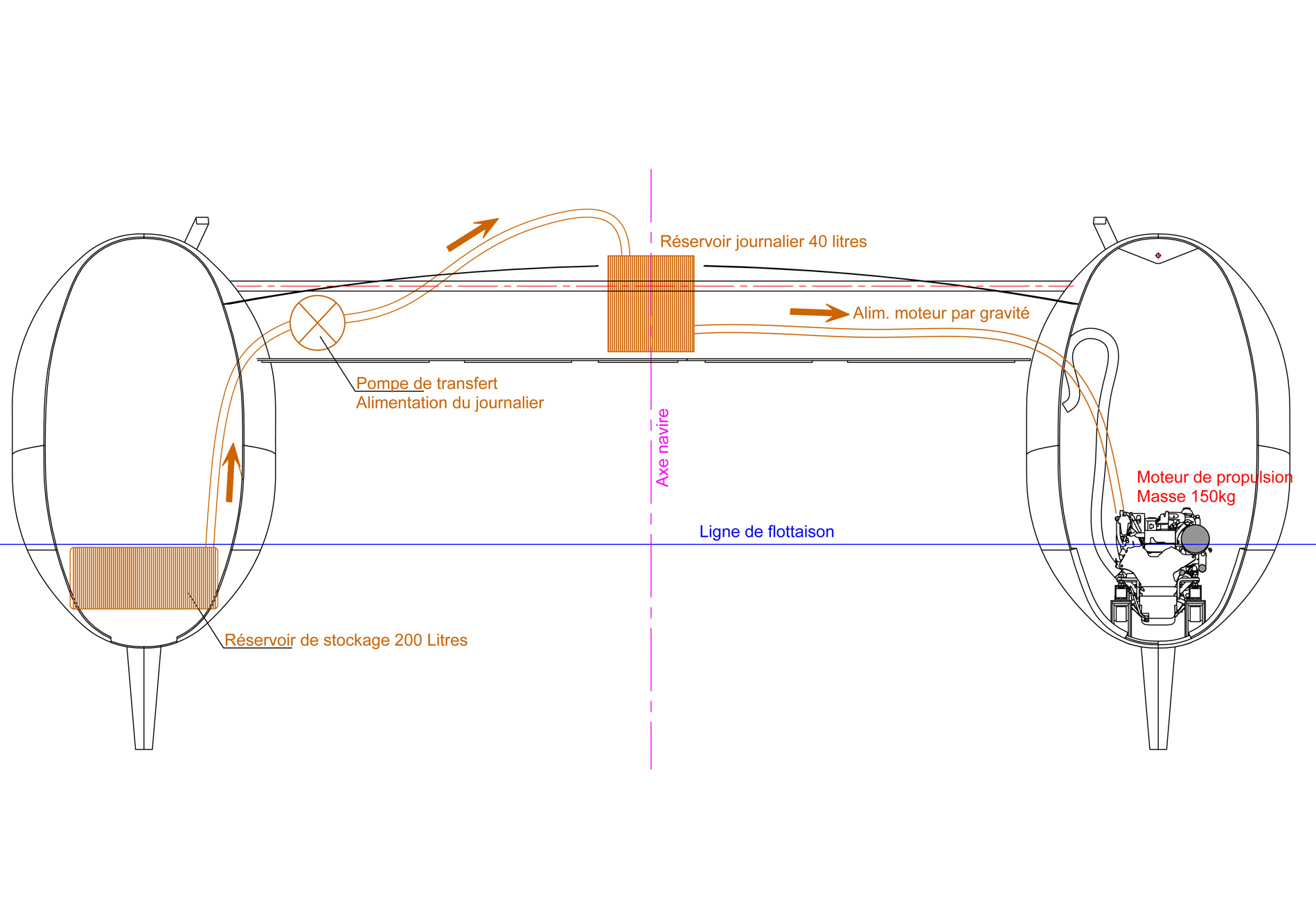

Regarding the 1st point: Of course, having a single propulsion engine significantly off-centres the catamaran’s centre of gravity. This solution should therefore be considered at the design stage of the boat, in order to balance the boat with compensating weights placed on the opposite side: galley, battery storage, various tanks, etc.

So on a catamaran where a 150kg propulsion engine has been positioned on the port hull axis, we can organise the installation of a 200L diesel storage tank symmetrically within the starboard hull (under a berth for example), and a so-called daily tank in the nacelle, on the ship’s axis, which will supply the engine simply by gravity!

It is therefore a skilful articulation of the onboard masses from the design and construction of the boat that will ensure a perfectly axial position of the vessel’s final centre of gravity.

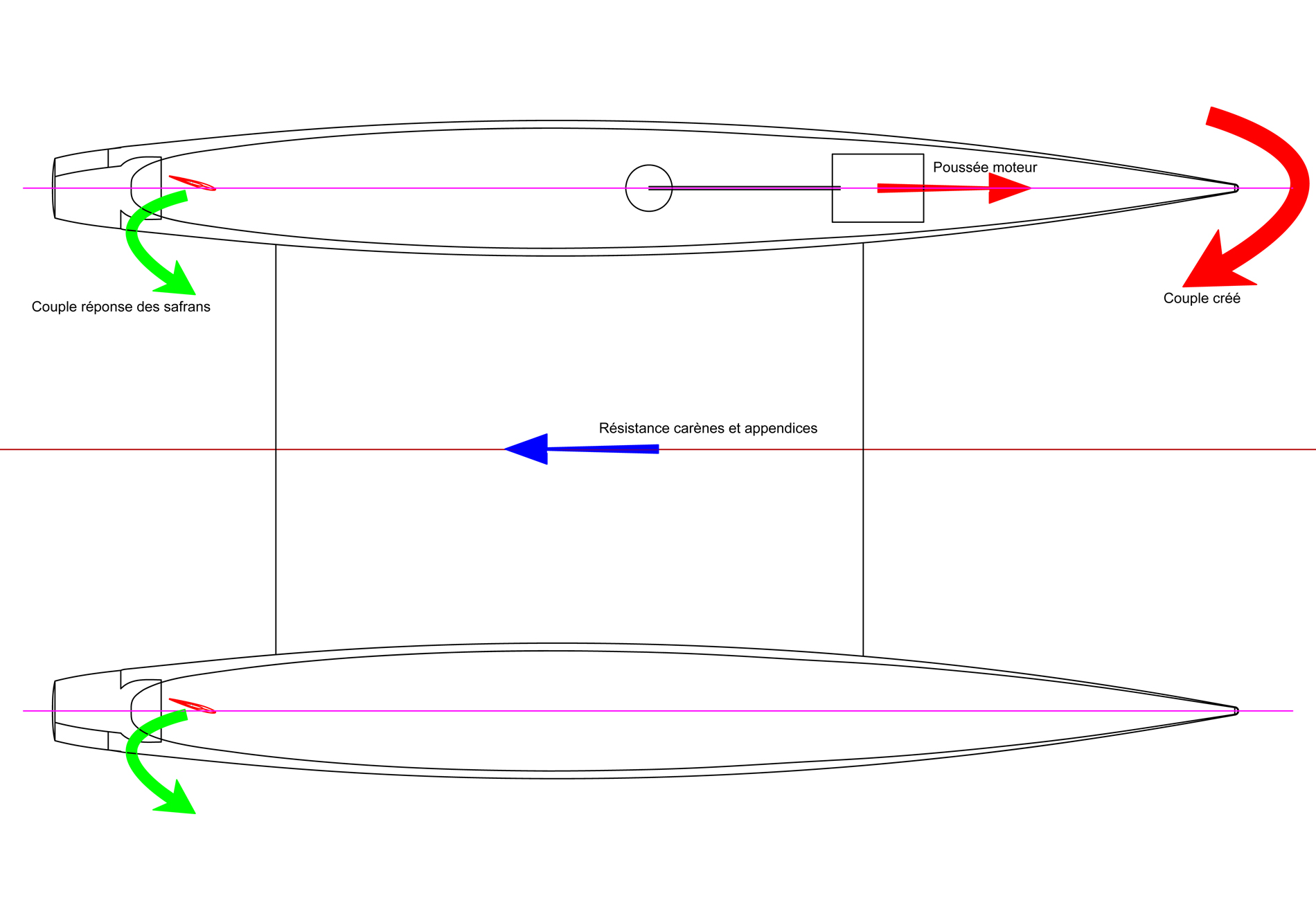

As far as the second argument is concerned, i.e. the propeller thrust axis being offset from the ship’s axis: it’s fair to say that a force couple is created between the propulsion of a single eccentric engine on a catamaran, with the resistance of two symmetrical hulls.

The resistance of the two hulls will be represented by a force positioned at the axis of the boat (between the two floats) while the thrust of the propeller will be eccentric along a float axis. If the engine is installed in the port float in this example, the torque created will tend to turn the boat to starboard when going forward (and vice versa when going astern).

It is mainly the rudders that will counteract this torque and allow the catamaran to go straight ahead. To do this, the rudders need to receive water at a minimum speed to remain operational (more on this later).

According to calculations carried out by our agency, on a 12-metre catamaran using a 30 hp engine (eccentric in a float) launched at full power (speed of 7 knots), the angle of the tiller necessary to counter this torque will be between 3° and 5° maximum. In comparison, a rudder can be pushed to +/- 35° on each side.

At the end of a tiller, this effort on the rudders will be equivalent to a pull of 12kg and around 25kg for a tiller-type autopilot with a smaller lever arm. For information, the thrust of a SIMRAD TP32 tiller pilot is 85kg.

A live test was carried out on one of our agency’s boats, the same 12-metre catamaran, equipped with a single Yanmar 3YM30 engine (30hp), a shaft line and a JProp propeller. When the boat is sailing, the angle of the tiller under pilot to counter the torque created by the eccentric engine is not visible to the naked eye. It is probably less than 5°, which confirms our preliminary calculations and verifies that the boat’s balance is perfectly preserved and involves negligible compensation from the steering gear.

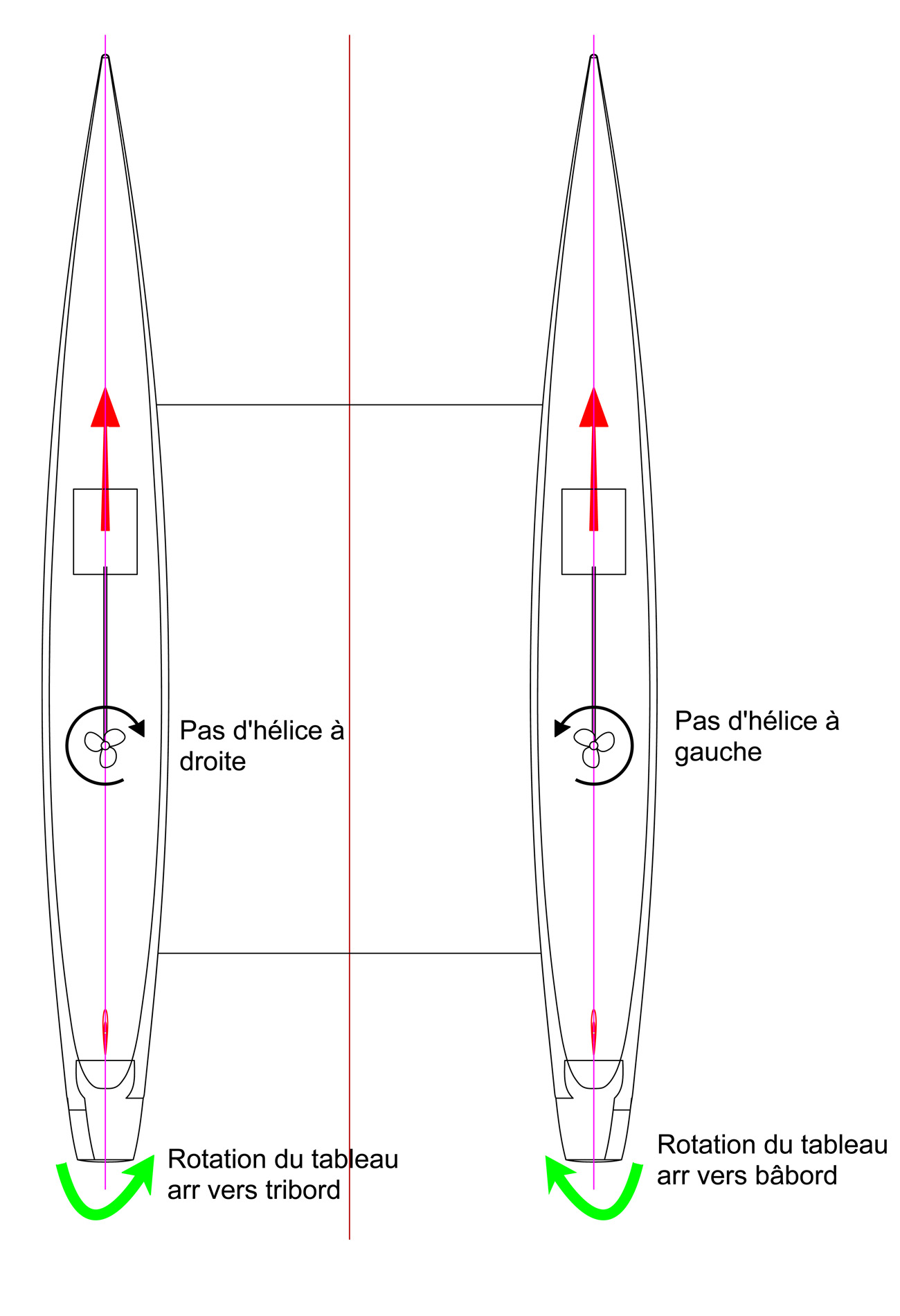

This torque can also be partially inhibited by an optimised study of the propulsion line: a propeller, by virtue of its pitch, has a natural tendency to turn the boat forwards and, even more intensely, astern. For example, a propeller with a clockwise pitch (the direction of rotation of the propeller is clockwise when the boat is viewed from aft to forward) will cause the stern of the boat to turn to the right when travelling forwards. The torque generated by the pitch alone will thus tend to turn the boat to port.

A propeller with an anti-clockwise pitch (anti-clockwise direction of rotation when looking at the boat from aft to forward) will of course have the opposite effect.

The aim of good propulsion line design will therefore be to combine a single engine positioned in a port float with a clockwise propeller so that the torque effects oppose each other (or vice versa). In practice, it should be remembered that in forward motion, the torque generated by the misalignment of the engine will be much greater than the torque generated by the pitch of the propeller… but this design will still go ‘in the right direction’.

In reverse, the effects of this sound design will be more noticeable because the effects of pitch are much greater.

The decision to position the engine in the starboard or port float is guided by the interior layout, of course (access for maintenance), but also by the exhaust system, since on a catamaran, the exhaust outlet will be on the inside of the hull to avoid it being swamped. If the engine exhaust outlet is positioned to the left when looking from aft to forward, then the engine will preferably be positioned in a starboard hull and the reverser chosen will ideally allow an anti-clockwise propeller to be fitted.

It has been shown that rudder compensation, combined with an appropriate propulsion line design, can easily inhibit the torque generated by the propulsion motor’s offset from the boat’s axis.

And at low speed?

At very low speeds, rudders produce very little force (as a reminder, the reaction of a rudder is proportional to the speed of the fluid squared). On the other hand, the propulsion torque is already active from the very first turns of the propeller. The result is a direct and instantaneous rotation of the boat when the engine is turned at zero speed.

As soon as the boat picks up speed (1 knot), it becomes manoeuvrable again and the torque can be corrected by progressive rotation of the two rudders, but this is still unacceptable when you want to get out of a berth, leave an anchorage or break your stern at the entrance to a marina, for example.

This confirms that an off-axis propulsion engine alone is not enough to manoeuvre a catamaran when speeds are too low (starts, arrivals, for example).

In addition to this propulsion motor, we need to add a complementary motor which we will call the ‘steering motor’.

The steering motor

The steering motor acts like a bow thruster on a monohull.

Its purpose is to counteract the rotation of the boat generated by (in our case, the torque due to the off-centre engine and) in the case of a monohull more generally, the dunnage (the thrust of the wind on the hull and its superstructure), or quite simply the pitch of its own propeller.

The energy requirements of this secondary engine remain much lower than those of the propulsion engine.

With a few exceptions, it is not intended to be used as a propulsion system in its own right (we saw earlier that if the propulsion motor was correctly sized, then its manoeuvrability when moving was perfectly satisfactory).

The purpose of the steering motor is, at low speed, to use the distance between the floats to generate a torque that will enable the catamaran to manoeuvre more easily. So, as with any catamaran, the boat will rotate in the desired direction as with a tank: one motor in forward gear, while on the opposite float, the motor will be operated in reverse.

Our secondary motorisation, here called the ‘steering motorisation’, will have to be placed in the opposite float to that of the propulsion motor, of course.

One of the major advantages of this configuration is the availability of an outboard and/or retractable steering motor. As this motor is mainly used in bays, anchorages and protected harbours to assist the boat’s steering during approach or departure manoeuvres, an outboard motor placed in one of the skirts, for example (for easy extraction if necessary), is still well positioned to play its role (little swell, so the propeller remains totally submerged). The main advantage of keeping a retractable motor is that, when at anchor, the propeller and shaft (long or short) can be extracted from the water, currents, seaweed etc. The result is that this secondary motorisation ages much better than on a ‘classic’ sailing catamaran, where the two shafts and propellers remain immersed and permanently exposed.

Having an assertively asymmetrical engine also means that you can have a hybrid engine that is more environmentally friendly. As the steering motor only requires a small amount of power and a limited period of use, an electric solution is perfectly suited (without the need for a battery pack or even an oversized generator). This hybridisation of the propulsion system offers a number of advantages:

– The possibility of claiming a clean, non-polluting engine, which in some parts of the world is becoming a real necessity. For example, certain Norwegian fjords are now off-limits to vessels powered exclusively by combustion engines. The autonomy of the steering engine could be studied to allow propulsion at low speed over a suitable period of time.

– The safety of having two sources of energy to power your catamaran. An internal combustion engine and an electric motor, this is an opportunity to separate the risks of polluted diesel affecting the two internal combustion engines of a catamaran with symmetrical propulsion.

– Finally, and probably above all, the possibility of using the steering motor as a one-off hydro generator. While we would like this engine to be retractable during long periods at anchor, it can nevertheless, like a conventional hydro generator, be fully lowered when the boat is under sail, in order to provide the basic function of recharging the on-board batteries. This avoids the need to invest in an additional hydro-generator, allows the sharing of supports and dedicated spaces in the skirts and therefore enables a perfect sharing of investments and on-board masses.

During tests on our 12-metre EPIC catamaran, we were able to check the ability of an electric motor to compensate for the torque generated by our propulsion motor.

We used the smallest TEMO model, which we installed on the skirt opposite the float housing the propulsion motor. This motor only has a thrust of 12kg and yet, positioned like a stern thruster, it was perfectly capable of completely countering (or even turning the boat in the opposite direction) the torque created by our eccentric propulsion motor. The EPIC catamaran’s smallest electric motor therefore acts as a ‘steering motor’.

Maxence Valdelièvre’s O Yacht Class6 catamaran has a similar engine layout.

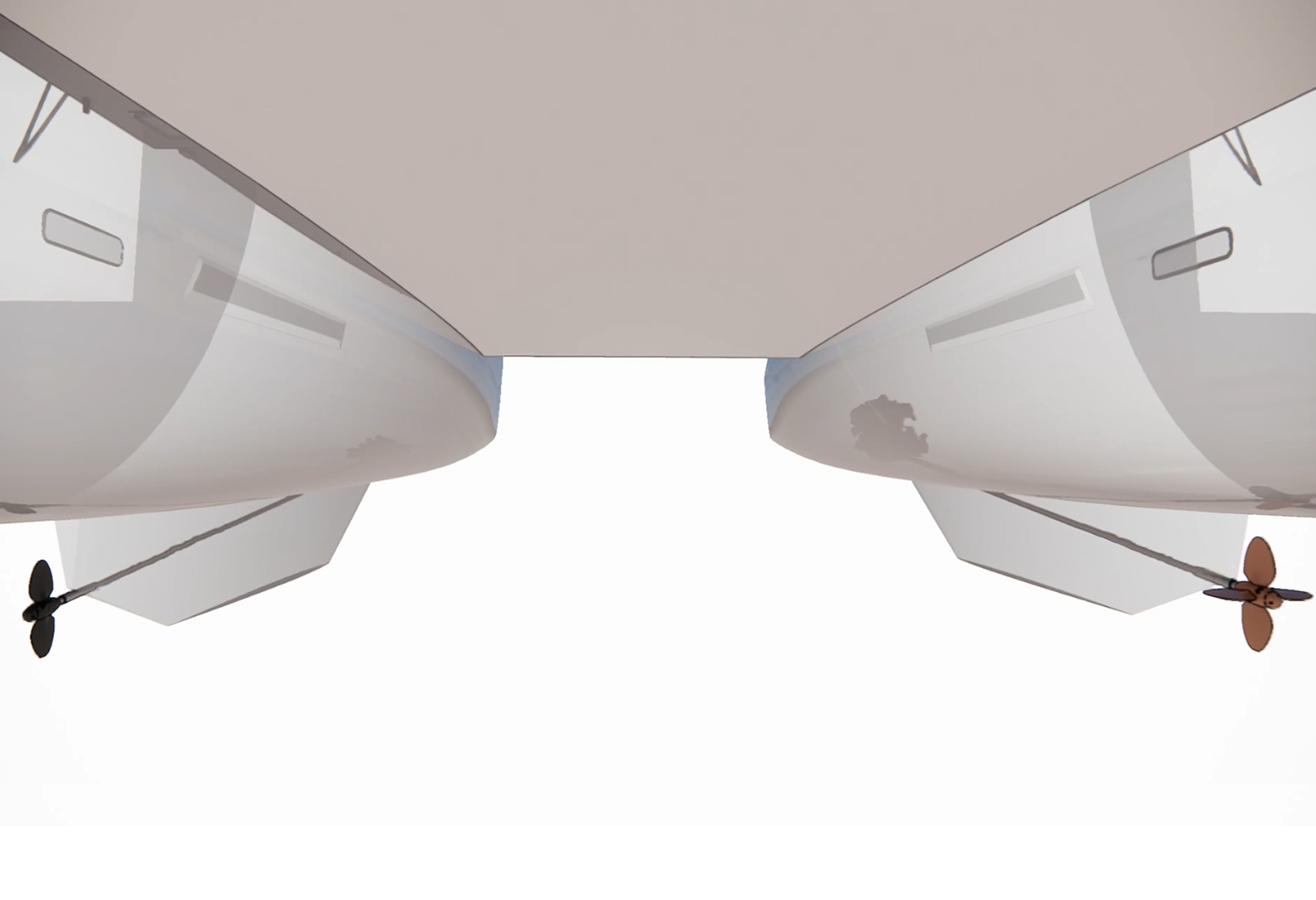

On this 63-foot sailing catamaran, the main engine consists of an 80hp inboard combustion engine with shaft line. The opposite hull houses a retractable electric motor acting as a hydrogenerator in a watertight shaft in the rear skirt.

On Maxence Valdelière’s catamaran, this is an 11kw RIM Drive Technology engine with a tunnel propeller. The engine weighs just 14kg. Of course, additional accessories such as batteries and a dedicated electrical circuit, solar panels and a dedicated charger/regulator all add up to a total weight of around 150kg. But it’s still perfectly competitive with a twin internal combustion engine… and the hydro-generator function is already integrated…

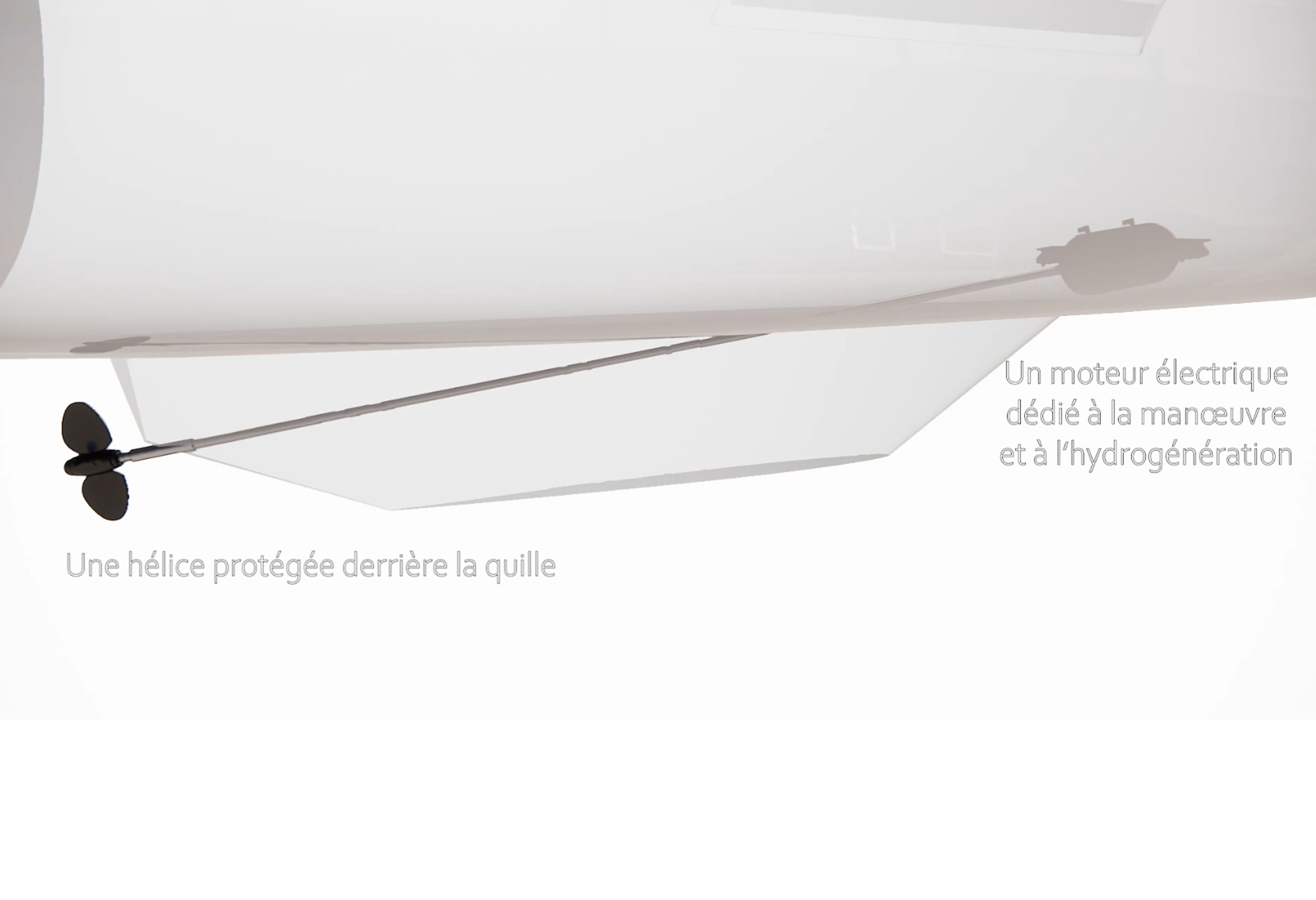

On other units, we may prefer a symmetry of shaft lines with a steering motor (here on the port side) stored in the float with the propeller shaft protected by the keel. In the case of the INSULA52′, this is a 10kW electric motor (combined with a 75hp combustion engine on the starboard side). Of course, this electric motor also acts as a hydro-generator when the boat is under sail! The electric motor on the port float takes up much less space than its internal combustion counterpart, and can easily be positioned under the floors of a converted area.

Conclusion of our CAP SUR n°1 :

Far be it from us to claim that this article is exhaustive on the subject of motor propulsion for sailing catamarans!

The aim was to present a simple, illustrated demonstration of how an alternative to the conventional propulsion of sailing catamarans on the market could be offered at the design stage.

Our ideal motorisation solution for an owner’s sailing catamaran would therefore look like this:

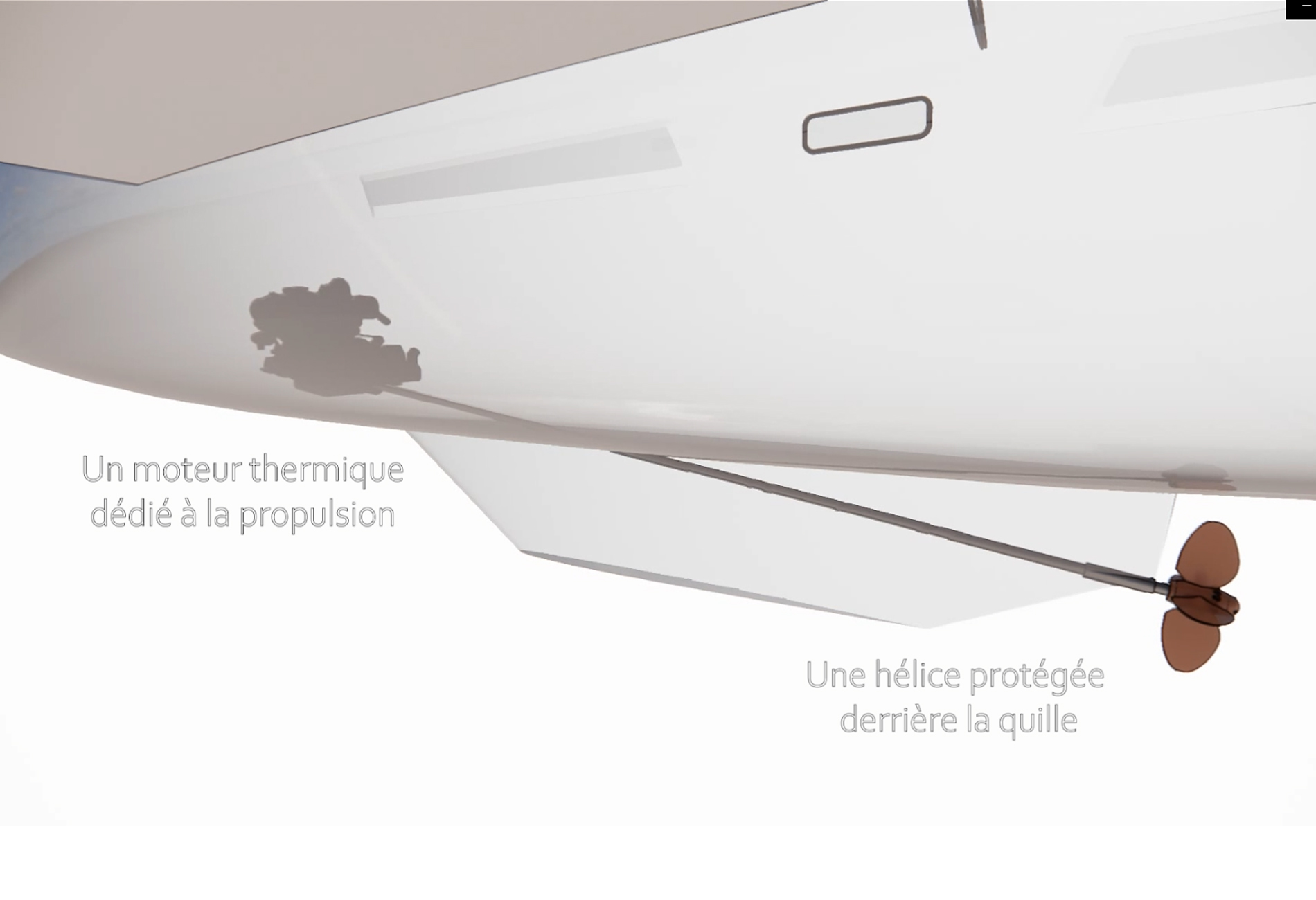

– An internal combustion engine, correctly sized as the boat’s sole drive, positioned in line with the shaft in one of the two floats, with a forward position to centre the masses and protect the shaft in the keel of the boat and the propeller just aft of it.

– An electric steering motor, autonomous and ideally liftable to optimise its longevity at anchor and in harbours. This motor will have a hydro-generation function to recharge the boat’s batteries (its own battery pack and the boat’s service pack) when the boat is under sail.

In our opinion, these two complementary engines combine the experience and safety of combustion engines, which are difficult to circumvent on a cruising yacht today, with the modernity and genuine technical and ecological advantages of an electric secondary engine….but of course everything remains open to debate!

See you soon for the next ‘Cap Sur